Bledsoe County Schools transform their energy training into cool savings

Brian Turner is up before the sun rises over the Sequatchie Valley in Middle Tennessee. His family is still sleeping as he drives through the thick morning fog to his father-in-law’s farm to help corral about 40 cattle for a morning weigh-in. He also sets out the feed and cuts some additional hay.

“Nothing you do on the farm you can do halfway. Farming is hard work,” says Turner. “When something breaks on a farm, you don’t buy new. You make it work and fix it.”

He has never shied away from hard work. On the contrary, Turner leans into it with a purpose. The people of Bledsoe County are raised to believe in hard work. It’s not uncommon for many to hold down two or three jobs to make ends meet in one of the state’s poorest counties. The county seat of Pikeville sits in the northern half of the valley, surrounded by the walls of the Walden Ridge to the east and Little Mountain to the west. The Sequatchie River passes through the eastern section of town. It’s an area rich in natural beauty but lacks the industry to keep many employed here.

“We make sacrifices when we stay here,” says Turner.

Unemployment hovers at 6%, nearly double the state average. Those who do find work have to travel outside the county. Turner considers himself fortunate to have a full-time job in town as maintenance, transportation and attendance supervisor at the Bledsoe County School District.

“We start in the morning with the bus runs. We always want to make sure the kids are getting to school safely,” says Turner. He then meets with his maintenance staff, overseeing three elementary schools, a middle school, a high school and a career tech center. Next, he works on the attendance records for each school and follows up with kids who are struggling to make it to class. The decade he’s worked at the school district has been eye-opening for Turner.

”I knew we had low-income families. But when I started working for the school district, it was way more than I expected. A lot of those families lean on the school to help them.”

School systems like Bledsoe County can become de facto childcare and meal service providers for struggling families. The district depends on property and sales tax dollars for its budget, but with just under 15,000 county residents, the tax base is insufficient.

“The amount of dollars the county can put back into the school system is minimal,” says Mike Partin, CEO and president of Sequachee Valley Electric Cooperative (SVEC). “The county school system is always looking for opportunities where they can bring in some money to help the school system to make a better school environment for the rural kids of Tennessee. That’s where TVA EnergyRight’s School Uplift made the difference.”

School Uplift helps districts make the energy efficiency grade

The School Uplift pilot kicked off in January 2020 with ten Tennessee schools, including Bledsoe County High School and Pikeville Elementary. Led by EnergyRight Program Manager Clay Hoover and his team, the 12-month program provides schools with comprehensive energy management training. The program has two specific goals: to reduce a school’s utility cost to redirect money back into funding education and to improve the learning environment for teachers, staff and students.

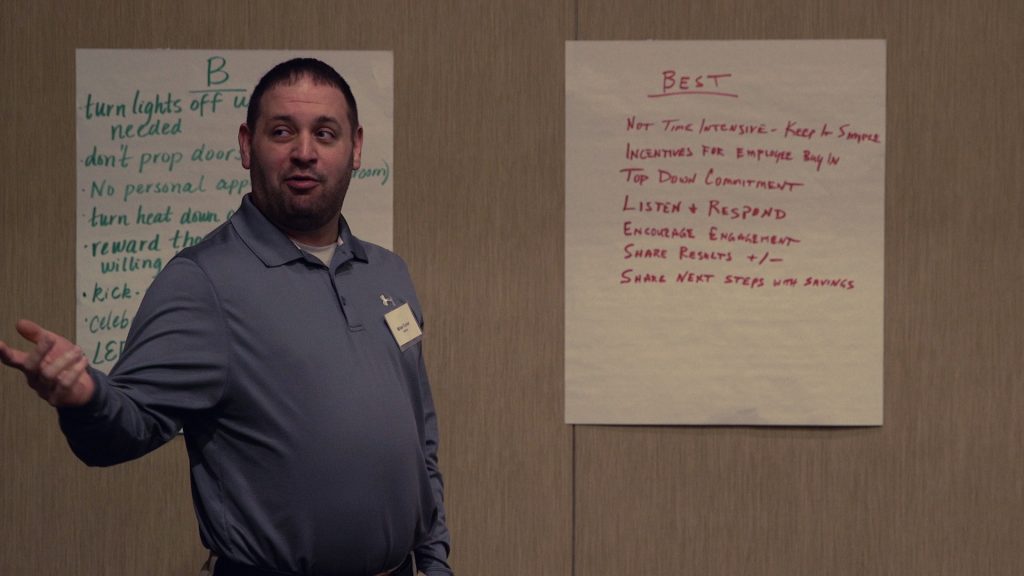

First, TVA EnergyRight engineers met with administrators from each school to conduct an energy audit and discuss energy efficiency pain points. School leaders then met throughout the year – in person and virtually – to learn about strategic energy management best practices, bounce ideas off each other and set energy efficiency goals. Hoover says these sharing sessions were beneficial for participants.

“A lot of schools were running equipment unnecessarily,” says Hoover. “They were leaving things on unnecessarily and had tight constraints on their control systems. By changing the operations, the schools can save a significant amount of energy.”

Hoover says Turner’s natural leadership shined in this setting. “Brian freely shared his expertise with the whole cohort,” says Hoover. “Other school directors looked to Brian for advice on how to implement energy-saving opportunities. You can quickly tell that he cares a lot about the school system and the kids and trying to improve the learning environment.”

Diane Elder, director of schools in nearby Pickett County, says Turner often called her early in the morning to exchange ideas. Many of the conversations happened while he was on the farm. “I’m barely waking up, and Brian’s talking excitedly on the phone about his ideas, and I can hear cattle mooing in the background.”

“We can’t have kids trying to learn in hot classrooms.”

Bledsoe County High School’s aging cooling tower has been Turner’s albatross. “We knew we had to replace the cooling tower because it was causing us lots of problems. TVA EnergyRight’s audit confirmed it was burning lots of energy,” says Turner.

A typical home HVAC system removes heat from inside the house and sends it to the outside unit that vents it. The high school uses a water system. It relies on a cooling tower to lower the temperature of the water and the air around it before sending the colder air through the school’s ductwork.

The cooling tower was always on the verge of breaking, and Turner was frustrated that he couldn’t fix it. “If the cooling tower stopped working, there would be no cold air in the building during the early summer, fall and spring months.”

Turner frequently pleaded before the school board for a new tower, but members were concerned about the $200,000 price tag. It’s roughly the maintenance team’s budget for an entire school year without factoring in salaries. “Being in the small rural districts, we don’t get a lot of extra money to spend on big maintenance projects.”

Turner thought he would never get the tower replaced. But then his schools successfully completed the School Uplift pilot and EnergyRight rewarded Turner and his team with two grants. The high school received a $200,000 building upgrades grant, and the elementary school was awarded a solar demonstration classroom grant. In addition, Tennessee’s Energy Efficient Schools Initiative matched EnergyRight’s building grant for a total of $400,000. “Tennessee has the best teachers in the nation, and we need our classrooms to match that standard to give students the best learning opportunity,” says Scott Slusher, EESI deputy director. “Making our schools more energy efficient will pay dividends for years to come.”

Turner says the grant money took an enormous weight off his shoulders. The new cooling tower was installed in October 2021 with enough money left over to complete other energy-saving projects.

“We were slowly trying to change the lighting and replace several older HVAC units, but the School Uplift grant helped us do that all at once,” says Turner.

EnergyRight says the pilot schools saved nearly 20% on their annual energy bills from behavior changes alone. Hoover says the additional facility upgrades will have lasting benefits. “LED lighting, energy efficient HVACs and the new cooling tower will further reduce energy consumption and costs over time. That empowers schools to redirect those savings to what matters most – educating children.”

Utility partnerships enhance the mission to help all customers

Hoover and Partin credit the strong partnership between EnergyRight and SVEC as one of the reasons for a successful School Uplift pilot.

“The only way you can achieve any kind of success is through partnership,” says Partin. “Unfortunately, there’s not one group or one agency that has enough resources to hit one out of the park. But when folks come together – SVEC standing shoulder to shoulder with Bledsoe County Schools and TVA EnergyRight’s School Uplift program – we’re starting to see the whole process bear fruit.”

Turner says his participation in School Uplift reshaped how he sees EnergyRight’s role. “When I started this program, SVEC was our electric provider, and TVA was our electric producer. After going through this program, they’re partners with us. They are the resources to help us.” The partnership has lasted. Turner says he still talks to the same TVA engineer who audited his schools at the beginning of the School Uplift pilot.

Opportunities are also expanding in Pikeville, highlighted by the recent announcement of a Minnesota-based manufacturing plant expanding its operations into Pikeville. It’s expected to produce 74 jobs and pump much-needed revenue into the community.

Nevertheless, Turner will still be back at the farm bright and early. Hard work doesn’t stop in Bledsoe County.

Related stories: